Supreme Court Ends CDC’s Eviction Moratorium

In a 6-3 unsigned decision,1 the United States Supreme Court ended the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) federal nationwide moratorium on evictions.

The Supreme Court held that the CDC does not have the authority to impose a nationwide moratorium on evictions:

It would be one thing if Congress had specifically authorized the action that the CDC has taken. But that has not happened. Instead, the CDC has imposed a nationwide moratorium on evictions in reliance on a decades-old statute that authorizes it to implement measures like fumigation and pest extermination. It strains credulity to believe that this statute grants the CDC the sweeping authority that it asserts.

The majority opinion concluded by stating that “Congress must specifically authorize” any further “federally imposed eviction moratorium.”

Justice Breyer, Justice Sotomayor, and Justice Kagan dissented. In the dissenting opinion, Justice Breyer wrote:

Applicants raise contested legal questions about an important federal statute on which the lower courts are split and on which this Court has never actually spoken. These questions call for considered decisionmaking, informed by full briefing and argument. Their answers impact the health of millions. We should not set aside the CDC’s eviction moratorium in this summary proceeding. The criteria for granting the emergency application are not met.

This was the second time the Supreme Court made a decision on the federal moratorium. In June, the Court allowed a broader version of the moratorium to remain in place through July. But, on August 3rd,the CDC renewed a narrower version of the moratorium for two more months.2

The plaintiffs in this case (who included the Alabama Association of Realtors) got a summary judgment from the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia vacating the moratorium on the ground that it is unlawful. But the District Court stayed its judgment while the Government pursued an appeal. The Supreme Court vacated the stay, rendering the judgment enforceable.

A summary judgment is a type of accelerated judgment. It is a judgment without a full trial. It is often termed a trial on paper.3 Like all judgments, a summary judgment must be enforced.4 But (as in this case) a summary judgment can be stayed, which means it cannot be enforced, pending a condition (here, the condition was appeal).

People’s responses to the Supreme Court’s decision are varied. For example, James Notta supports the decision because some tenants “are taking advantage of the situation”:

Unfortunately, there are those who are taking advantage of the situation and could pay. Why should the landlord's be punished. I imagine there are quite a few of them they can't afford covering their rental property as well as the mortgage on their current residence.

— James.notta (@notta_james) August 27, 2021

My friend echoed Notta’s comment when he asked, “My tenants say they can’t pay my rent and then fly to the Middle East for a vacation. What can I do? How can I pay my mortgage?”

In contrast, @alexrichardon feels the decision is “cruel” because “there’s still a pandemic going.”

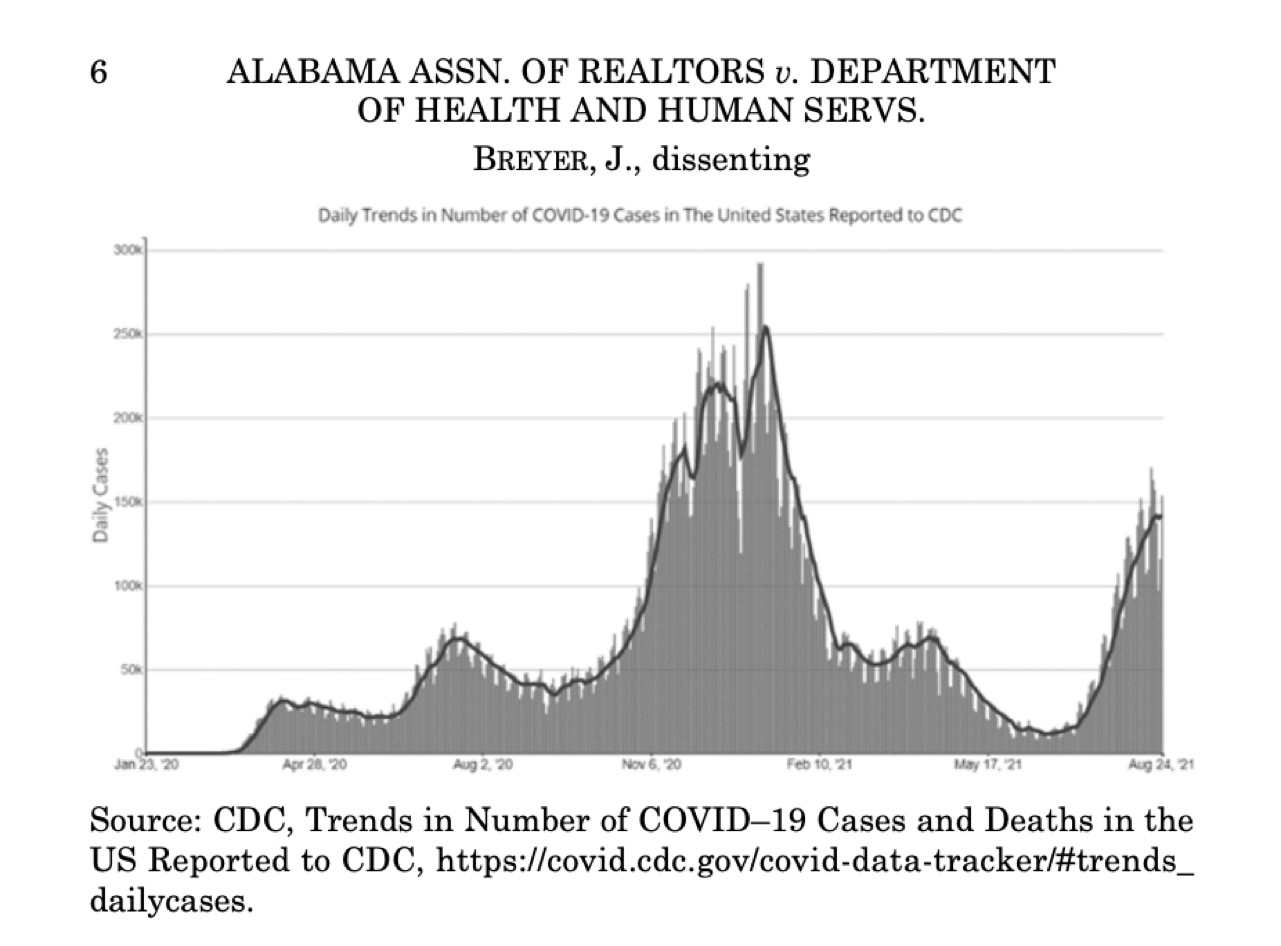

@alexrichardon’s comment alludes to Justice Breyer’s dissent. Justice Breyer shares the following CDC chart and states, “Absent the current stay, the CDC projects a strong ‘likelihood of mass evictions nationwide’ with public-health consequences that would be ‘difficult to reverse’”:

Personally, I have some reservations about the decision:

(1) The Supreme Court’s earlier decision kept the lower court’s stay, but now the COVID-19 Delta variant is worse and the Court lifts the stay.

(2) How was a summary judgment appropriate in a case where the statute at issue can be and has been interpreted in more than one way? As the dissent states:

lower courts have split on this question. . . . Given the split among the Circuits, it is at least hard to say that the Government’s reading of the statute is “demonstrably wrong.” . . . At minimum, there are arguments on both sides.

Despite these reservations, I strongly support the result of the decision:

(1) I don’t think a federal government agency should intrude in landlord-tenant matters, which are traditionally state matters. As the majority opinion states, “The moratorium intrudes into an area that is the particular domain of state law: the landlord-tenant relationship.”

The Court merely struck down a federal moratorium imposed by a federal agency, but it explicitly invites Congress to impose a moratorium:

It would be one thing if Congress had specifically authorized the action that the CDC has taken. . . . It is up to Congress, not the CDC, to decide whether the public interest merits further action here.

(2) If the Court didn’t proscribe the CDC, the CDC’s powers would be unchecked. As the majority opinion states:

Even if the text were ambiguous, the sheer scope of the CDC’s claimed authority under §361(a) would counsel against the Government’s interpretation. . . . Indeed, the Government’s read of §361(a) would give the CDC a breathtaking amount of authority. It is hard to see what measures this interpretation would place outside the CDC’s reach, and the Government has identified no limit in §361(a) beyond the requirement that the CDC deem a measure “necessary.” 42 U. S. C. §264(a); 42 CFR §70.2. Could the CDC, for example, mandate free grocery delivery to the homes of the sick or vulnerable? Require manufacturers to provide free computers to enable people to work from home? Order telecommunications companies to provide free high-speed Internet service to facilitate remote work?

Ultimately, I agree with the Wall Street Journal’s Editorial Board assessment of this decision as “a sharp legal rebuke to [President Biden’s] abuse of executive power.”5 The Court ended eviction moratoriums by the CDC and put the ball in Congress’ court.

-

Alabama Association of Realtors v. Dep’t of Health and Human Services, 594 U.S. ___ (2021). ↩

-

For some procedural history leading up to the current decision, see Alabama Association of Realtors v. Department of Health and Human Services, SCOTUS Blog. ↩

-

See, e.g., Michele L. Maryot, The Trial on Paper: Key Considerations for Determining Whether to File a Summary Judgment Motion, Litigation, Volume 35, Number 3, Spring 2009. ↩

-

A non-money judgment can be enforced by contempt proceedings. ↩

-

The Editorial Board, Justice Kavanaugh Replies to Mr. Biden, WSJ, Aug. 27, 2021 (via Apple News). ↩